Bring Back GCOM?

04 Aug 2015

The weekend before last, I started working on a simple graphical operating environment built on top of SDL. I wanted to explore the design space, and test some hypotheses I had. In the process, I learned quite a bit more than I ever expected. This article summarizes one important lesson that I learned. I’ll blog about other lessons as time permits.

I’m not one to support Big Design Up Front, but I will insist on this one. Get this right, and your design will virtually write itself. Get this wrong, and you’ll probably want to consider a farming career in as little as a year.

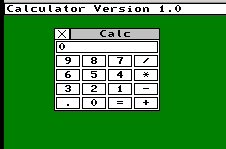

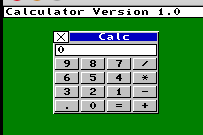

My GUI is, so far, pretty simple and modular. It looks nice enough, at least for the simple 4-function calculator I used to evolve it.

You’ll notice that the imagery is pretty flat, which is fine for development, but not for today’s appliance-oriented UI trends. What if we want to change the rendering to draw a more 3D appearance, such as what was popular in the late 90s?

To accomplish this, we would need to, at the very least,

replace objects.c with a version that

knew how to draw the controls correctly.

In this quick prototype,

that’s a simple task of renaming or relinking files, and then recompiling.

But if the majority of the GUI resides in ROM,

which is my intention for the Kestrel, that’s clearly a problem.

To make use of a new visual design,

the user really doesn’t want to have to replace his or her ROM image.

Even if we used a disk-resident GUI environment,

we still don’t want the user to have to recompile everything.

It would be super nice if the user could just select a theme from a preferences editor.

COM for reducing coupling between cohesive modules

Simply put, this is a problem of linkage.

We need a way of identifying our dependencies at run-time.

As it happens, several software modularity technologies exist that are designed to cover this problem domain.

In 1985, Amiga, Inc. introduced AmigaOS, whose entire operating system is built on top of a runtime that mapped names to libraries, devices, and other services.

Applications could request services from a module without having to link against it directly via the OpenLibrary system call.

Once the library was open, you used a jump table to access its functionality.

This allowed the Amiga to support dynamic linking in an era when “shared objects” weren’t even invented yet.

If you’ve never used an Amiga before, yet this sounds awfully familiar,

it’s because in 1993, Microsoft unveiled Component Object Model.

It is based more or less on the exact same concept.

COM is strictly a superset of the Amiga’s model for code reuse.

Why COM appeals to me

COM is significantly lighter-weight than many other alternatives. CORBA technically predates COM by about 2 years or so, but it focuses on enterprise-scale service distribution in a heterogenious mixture of computing resources (something we call a “cloud” these days). As a result, it was (without non-compliant extensions like IBM’s SOM and direct-to-SOM compilers) impossible to implement components using CORBA without instantiating an ORB (server) event loop. Clearly, this impedes CORBA’s suitability for desktop computing applications looking for lightweight modularity. Things have improved somewhat; however, the prospect of using Python objects directly in a C application using CORBA as the component solution without multiple ORB event loops remains elusive to this day. It also, at the time, lacked an easy to use directory service for locating factories, objects, etc.

Several characteristics make COM ideal for loose coupling in GUI applications. First, all programming languages today talk C, and C happens to be the standard ABI for COM. So, when you call a method on a COM interface, even in the most obscure of languages, you eventually end up speaking the same language as everyone else. This is what Microsoft means when they talk about “binary-standard compatibility.” This is what CORBA never had, and is what killed it on the desktop.

Second, and perhaps most importantly, it offers a standard directory service that’s easy to use.

You go to COM’s runtime environment and say, “I need class AAAAAAAA-BBBB-CCCC-DDDD-EEEEEEEEEEEE”,

where AAAAAAAA-BBBB-CCCC-DDDD-EEEEEEEEEEEE refers to, say in our example, a layout or theme driver.

The COM runtime will look through its registry,

mapping that obnoxiously long number to an implementation of the behavior it represents.

It’ll load the module from persistent storage if required.

Note that, while there’s significant overlap,

“COM classes” are not “object classes” in the traditional object-oriented sense.

And, that’s OK;

modules are not classes anyway.

The neat thing about COM over AmigaOS libraries is that COM permits multiple implementations of a class to exist on the system at once, and a single registry entry permits you to select one among them all. Therefore, a preference editor can scan the registered list of theme drivers by simply querying all classes to see if they support the theme driver service, and based on the results, present a convenient user interface to the user. When the user makes a selection, that “pointer” entry is updated, and from that moment forward, newly run programs will run with the new theme. With an event notification system, existing programs can adjust as well.

One cannot do this as easily with stock AmigaOS libraries, because

a library’s name dictates both its interface and its implementation.

To accomplish the same with plain libraries,

you’ll need to store theme drivers in a special directory,

each with different names,

and have a different directory service designed to

return the user’s preferred theme driver name (including its path),

to be passed into OpenLibrary for access.

It’s also more fragile:

nothing prevents me from copying a widget toolkit library into a directory intended to only contain theme drivers.

As long as you don’t go all hog-wild trying to support aggregation,

COM largely automates separation of API and implementation naming, since it formally defines the two-step resolution process explicitly.

In addition, COM’s use of the QueryInterface method provides an extra defense against the fragility of Foo libraries appearing where Bars are expected.

Lesson learned

If your GUI architecture isn’t built on top of COM or a similarly inspired system, it’s going to suffer from modularity limitations in the future. For embedded work, this might be OK. I don’t consider it OK for general purpose computing on the Kestrel, which explicitly aims to not hinder or restrict its users in an unduly manner.

The Kestrel’s GUI should be built on top of COM technology or some similar means of decoupling separately compiled modules from each other.

Should I drag GCOM out of mothballs?

As it happens, I had cloned a purely in-process implementation of COM back in early 2000s. I called it GCOM, for Generic Component Object Model. It seems like it might be worth taking it out of cold storage again, and applying it for use in Kestrel’s operating environment.

I remain undecided if I want to commit to using COM for working with the Kestrel’s GUI APIs, but I know one thing is for sure: relying solely on shared object libraries has never scaled without some outside help. And, this is one technical decision that will seal the developer experience and, indirectly, user experience fates pretty much forever.

No pressure.

Samuel A. Falvo II

Twitter: @SamuelAFalvoII

Google+: +Samuel A. Falvo II

About the Author

Software engineer by day. Amateur computer engineer by night. Founded the Kestrel Computer Project as a proof-of-concept back in 2007, with the Kestrel-1 computer built around the 65816 CPU. Since then, he's evolved the design to use a simple stack-architecture CPU with the Kestrel-2, and is now in the process of refining the design once more with a 64-bit RISC-V compatible engine in the Kestrel-3.

Samuel is or was:

- a Forth, Oberon, J, and Go enthusiast.

- an amateur radio operator (KC5TJA/6).

- an amateur photographer.

- an intermittent amateur astronomer, astrophotographer.

- a student of two martial arts (don't worry; he's still rather poor at them, so you're still safe around him. Or not, depending on your point of view).

- a former semiconductor verification technician for the HIPP-II and HIPP-III line of Hifn, Inc. line-speed compression and encryption VLSI chips.

- the co-founder of Armored Internet, a small yet well-respected Internet Service Provider in Carlsbad, CA that, sadly, had to close its doors after three years.

- the author of GCOM, an open-source, Microsoft COM-compatible component runtime environment. I also made a proprietary fork named Andromeda for Amiga, Inc.'s AmigaDE software stack. It eventually influenced AmigaOS 4.0's bizarre "interface" concept for exec libraries. (Please accept my apologies for this architectural blemish; I warned them not to use it in AmigaOS, but they didn't listen.)

- the former maintainer and contributor to Gophercloud.

- a contributor to Mimic.

Samuel seeks inspirations in many things, but is particularly moved by those things which moved or enabled him as a child. These include all things Commodore, Amiga, Atari, and all those old Radio-Electronics magazines he used to read as a kid.

Today, he lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with his beautiful wife, Steph, and four cats; 13, 6.5, Tabitha, and Panther.